Collections

George and Charlotte Gibson

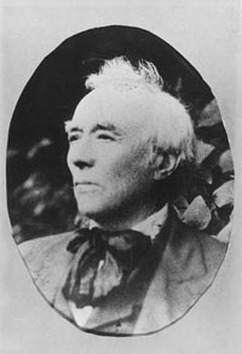

George William Gibson Sr. (1829 - 1913), was born to a family of market gardeners in Boston, Lincolnshire, England. He ran away to sea at the age of twelve, eventually retiring from the Royal Navy as a lieutenant. Still young, George emigrated to North America, married Augusta Charlotte Purdee, and settled in Chatham, Ontario. The couple took up market gardening and met with success. Meanwhile, their family grew until there were eight children: George William (b. 1862), Eliza (b.1863), Mary Ann (b.1865), Ralph Henry (b.1868), Emma-Jane (b.1872), Charlotte "Lottie" Augusta (b.1865), Harriet Elizabeth (b.1878), and Ellen "Nellie" Matilda (b.1881).

But George wanted land of his own. He and his sons headed west to pre-empt land to farm. Pre-emption laws of the time allowed for white settlers to claim large tracts of land in hopes of encouraging farming and the development of settlements. At this time, First Nations and Chinese settlers were barred from pre-empting land through discriminatory legislation which was designed to benefit certain settlers, and disadvantage others.

The Gibsons passed through Vancouver before travelling to Nanaimo to look for a suitable place. Though they found nothing there, they did not give up the search. An acquaintance suggested they investigate visit Howe Sound; encouraged, the resourceful Gibsons built a small, flat-bottomed sloop on a Nanaimo beach, christened her the Swamp Angel, and set off. They crossed the Salish Sea the next day and landed in the traditional, unceded territory of the Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) Nation, at what is now Gibson's Landing, on the morning of May 24th, 1886. George Sr. liked what he saw, and at fifty-seven years of age, pre-empted District Lot 686. His son George Jr. staked D.L. 685; these two lots together covered much of what is now known as Lower Gibsons. Ralph chose to settle on Paisley Island.

George Sr. was very active in the community that developed here. He donated land for the town's first school, and, after Charlotte's death in 1910, he donated land for a family cemetery and a Methodist church. The church is no longer standing, but the cemetery, located at the corner of School Road and Gibsons Way (by the Gibsons Visitors Information Centre) can still be visited. Gibson also served as postmaster for several years. The settlement was named Gibson's Landing in 1907 in honour of this hardworking pioneer.

But George wanted land of his own. He and his sons headed west to pre-empt land to farm. Pre-emption laws of the time allowed for white settlers to claim large tracts of land in hopes of encouraging farming and the development of settlements. At this time, First Nations and Chinese settlers were barred from pre-empting land through discriminatory legislation which was designed to benefit certain settlers, and disadvantage others.

The Gibsons passed through Vancouver before travelling to Nanaimo to look for a suitable place. Though they found nothing there, they did not give up the search. An acquaintance suggested they investigate visit Howe Sound; encouraged, the resourceful Gibsons built a small, flat-bottomed sloop on a Nanaimo beach, christened her the Swamp Angel, and set off. They crossed the Salish Sea the next day and landed in the traditional, unceded territory of the Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish) Nation, at what is now Gibson's Landing, on the morning of May 24th, 1886. George Sr. liked what he saw, and at fifty-seven years of age, pre-empted District Lot 686. His son George Jr. staked D.L. 685; these two lots together covered much of what is now known as Lower Gibsons. Ralph chose to settle on Paisley Island.

George Sr. was very active in the community that developed here. He donated land for the town's first school, and, after Charlotte's death in 1910, he donated land for a family cemetery and a Methodist church. The church is no longer standing, but the cemetery, located at the corner of School Road and Gibsons Way (by the Gibsons Visitors Information Centre) can still be visited. Gibson also served as postmaster for several years. The settlement was named Gibson's Landing in 1907 in honour of this hardworking pioneer.

Charlotte Gibson, nee Charlotte Augusta Purdee (1839 - 1910) is known not only as a founder of Gibson’s Landing but as a skilled midwife and nurse. The details of Charlotte’s birth and background in the USA are contested but we know that she married George Gibson in 1859 at age nineteen and moved to Ontario. By the time she arrived in Gibson’s Landing in 1886 she had given birth to eight children. Settlers in the area went to Charlotte when they were sick or when a baby was due. She also went by canoe to attend to members of the Squamish Nation for up to a week at a time. They nicknamed her the “Swamp Angel” after her husband, George Gibson’s boat.

The Sunshine Coast Museum and Archives currently displays a glass oil lamp of turquoise blue inset with pressed flowers which Charlotte Gibson brought with her from Ontario. Its value rests not only in its translucent beauty but the fact that several babies were born with the help of its light. The BC Archives hold 40 registered births on the Sunshine Coast between 1889 and 1903. 33 of these birth registrations have been scanned and digitized for public view. These 33 documents detail such information as the birthweight and medical attendant present. Of these 33 births, Mrs. Gibson is listed as midwife to 15 births – 8 of which were her own grandchildren. Charlotte’s daughter “Lottie” McCombs is also recorded as a midwife. Only 4 of the 33 births were attended by a physician, and 6 had no medical attendant present. If these 33 documents are to be taken as a representative sampling of the 40 total registered births in the early settler period it is clear that Charlotte was an active midwife in the community.

Charlotte Gibson lived in the Victorian era and it is evident that she embodied the spirit of the age through her hard work, devotion to duty, charity, and personal sacrifice. When smallpox broke out in 1892, she didn’t hesitate to take in a local man who had a very advanced case of the disease. Arthur Hyde (now buried in the Gibson family plot) had unknowingly contracted the virus while supervising the quarantine of Chinese immigrants aboard the Empress of Japan.

Victims of smallpox may initially suffer delirium or violent outbursts, and survivors may be pockmarked or blinded. Until eradicated in 1980, the disease was endemic to most global populations except Indigenous ones. A previous outbreak in 1862 had greatly reduced the Sunshine Coast Indigenous population to less than 200 people who were either immune or vaccinated. It is not surprising that the 1892 outbreak led to the desertion of the Ch’kw’elhp village in Gibsons. Even in populations with acquired immunity, the death rate is 30%.

Despite Charlotte’s best efforts, Arthur Hyde died on May 22, 1892. Two weeks later, she and her entire family (except her son Ralph who was living next door) came down with the dreaded disease. At its worst point there were 11 people ill with smallpox in the Gibson home. It is not known whether the Gibson family had been vaccinated. All family members survived, but for a time Charlotte’s daughter Lottie (whose head had been shaved to reduce fever), was not expected to live.

The Gibson home was officially quarantined as a pest-house, and the Provincial Government sent regular deliveries of food and two nurses (Sisters Frances and Jessie from St. James’s Anglican Church in Vancouver) to care for the family. One of these nurses developed smallpox herself, but survived. A news article of the time states that an additional male nurse was sent to assist the Sisters “as ten patients are more than two lady nurses can attend to”.

After the disease abated, it has generally been understood that the Gibson family home and their belongings were burned upon orders issued August 14th 1892. However, local knowledge indicates that Charlotte’s sewing machine was blackened in a smallpox fumigation. Indeed, a recently discovered news article states that orders to burn the home were changed to “a thorough fumigation” only. Here, four pounds of sulphur for every 1000 cubic feet of air were burnt in open pans throughout the house. Clothing was soaked in a solution of bi-chloride of mercury and afterwards boiled in hot water. Sulphur is also known as brimstone, and there are reports from the time detailing accidental deaths from sulphur fumigation as well as the “wholesale destruction of furniture by official fumigators”. The Sunshine Coast Museum and Archives displays a sewing machine from this era with damage to the enamel finish and some blackening of its wooden frame. Anyone with information which might assist us in the identification of this machine as Charlotte’s or not, is gratefully asked to contact the museum.

The Sunshine Coast Museum and Archives currently displays a glass oil lamp of turquoise blue inset with pressed flowers which Charlotte Gibson brought with her from Ontario. Its value rests not only in its translucent beauty but the fact that several babies were born with the help of its light. The BC Archives hold 40 registered births on the Sunshine Coast between 1889 and 1903. 33 of these birth registrations have been scanned and digitized for public view. These 33 documents detail such information as the birthweight and medical attendant present. Of these 33 births, Mrs. Gibson is listed as midwife to 15 births – 8 of which were her own grandchildren. Charlotte’s daughter “Lottie” McCombs is also recorded as a midwife. Only 4 of the 33 births were attended by a physician, and 6 had no medical attendant present. If these 33 documents are to be taken as a representative sampling of the 40 total registered births in the early settler period it is clear that Charlotte was an active midwife in the community.

Charlotte Gibson lived in the Victorian era and it is evident that she embodied the spirit of the age through her hard work, devotion to duty, charity, and personal sacrifice. When smallpox broke out in 1892, she didn’t hesitate to take in a local man who had a very advanced case of the disease. Arthur Hyde (now buried in the Gibson family plot) had unknowingly contracted the virus while supervising the quarantine of Chinese immigrants aboard the Empress of Japan.

Victims of smallpox may initially suffer delirium or violent outbursts, and survivors may be pockmarked or blinded. Until eradicated in 1980, the disease was endemic to most global populations except Indigenous ones. A previous outbreak in 1862 had greatly reduced the Sunshine Coast Indigenous population to less than 200 people who were either immune or vaccinated. It is not surprising that the 1892 outbreak led to the desertion of the Ch’kw’elhp village in Gibsons. Even in populations with acquired immunity, the death rate is 30%.

Despite Charlotte’s best efforts, Arthur Hyde died on May 22, 1892. Two weeks later, she and her entire family (except her son Ralph who was living next door) came down with the dreaded disease. At its worst point there were 11 people ill with smallpox in the Gibson home. It is not known whether the Gibson family had been vaccinated. All family members survived, but for a time Charlotte’s daughter Lottie (whose head had been shaved to reduce fever), was not expected to live.

The Gibson home was officially quarantined as a pest-house, and the Provincial Government sent regular deliveries of food and two nurses (Sisters Frances and Jessie from St. James’s Anglican Church in Vancouver) to care for the family. One of these nurses developed smallpox herself, but survived. A news article of the time states that an additional male nurse was sent to assist the Sisters “as ten patients are more than two lady nurses can attend to”.

After the disease abated, it has generally been understood that the Gibson family home and their belongings were burned upon orders issued August 14th 1892. However, local knowledge indicates that Charlotte’s sewing machine was blackened in a smallpox fumigation. Indeed, a recently discovered news article states that orders to burn the home were changed to “a thorough fumigation” only. Here, four pounds of sulphur for every 1000 cubic feet of air were burnt in open pans throughout the house. Clothing was soaked in a solution of bi-chloride of mercury and afterwards boiled in hot water. Sulphur is also known as brimstone, and there are reports from the time detailing accidental deaths from sulphur fumigation as well as the “wholesale destruction of furniture by official fumigators”. The Sunshine Coast Museum and Archives displays a sewing machine from this era with damage to the enamel finish and some blackening of its wooden frame. Anyone with information which might assist us in the identification of this machine as Charlotte’s or not, is gratefully asked to contact the museum.

|

Charlotte Gibson's lamp, used in the their salon/dining room. It was brought to West Howe Sound in 1886.

|